On Multidisciplinarity…

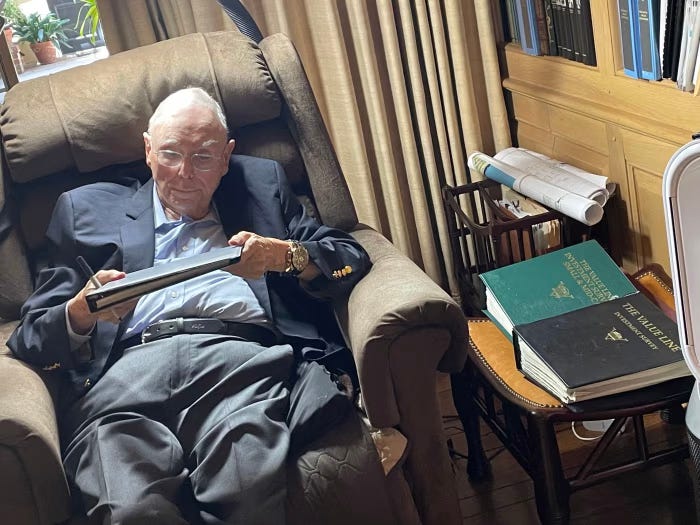

“You have a moral duty to make yourself as un-ignorant and as un-stupid as you possibly can.” - Charlie Munger

The so-called seeds for this article were sown about 3 years ago while discussing my dissertation topic with my professors. I wanted to look at finance and geopolitics together but was told not to do so because, the professors guiding me weren’t equipped to deal with the subject.

That made me ask a question, “Is this the way people are supposed to understand the world around them?”

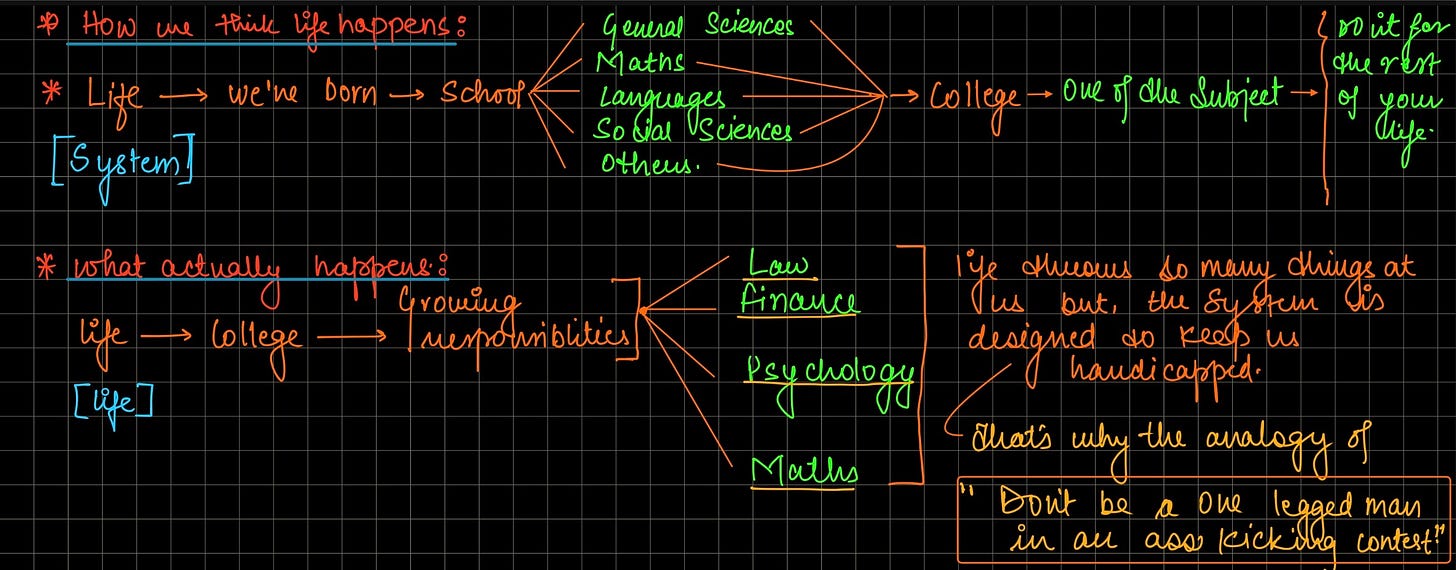

Later on while reading, Poor Charlie’s Almanack, I came across an analogy that frames this situation quite well; “Are we supposed to live like a ‘one-legged man in an ass-kicking contest?’1

So, this is my take on the subject of multidisciplinarity.2

The Plot

I have always struggled with the way we are taught to ‘intellectually’ die.

As kids we study a lot of subjects but as we grow older we are told—or rather, the system is designed in such a way that forces us—to narrow down what we learn or do even though this is totally opposite to how we actually live.

But if we look around us, as we get older our lives get more and more multidisciplinary—We deal with law (e.g., traffic laws, contracts), finance (e.g., day-to-day budgeting, loans, investing, etc.), psychology (e.g., dealing with humans around us, dating, mating, etc.), maths (e.g. other day, I was calculating volume of a truck to calculate the cost of gravel). You can’t negate the fact that more than one discipline is a deciding factor in how we get to live life.

We can think of it like this: As practical things around us gets multi-disciplinary the theory and things we practice gets mono-disciplinary.

This in my opinion is not a good way to live. If we live our lives like this, we often find ourselves depending on the “expertise” of others. And more often than not, we will find that, it’s like asking our barber whether we need a haircut—rarely the answer would be “no”.

Why do it?

Simple: It’s a better way to live; it’s an intelligent way of dealing with things that life throws at us.

I’ll let Charlie Munger tell you: “You have to learn many things in such a way that they’re in a mental latticework in your head and you try that, I solemnly promise that one day most will correctly come to think, “Somehow I’ve become one of the most effective people in my whole age cohort.” In contrast, if no effort is made toward such multidisciplinarity, many of the brightest of you who choose this course will life in the middle ranks, or in the shallows.” (Emphasis mine)

And I’m a bit biased towards this, as I don’t want to “die at 25 and wait till I’m buried at the age of 75”.

Multidisciplinary approach makes you antifragile. Anything generational3 needs to evolve so it can survive a changing environment—and in today’s world, being genuinely curious across various disciplines is a sure-shot way to remain relevant. This is more a necessity in the world of AIs and LLMs.

Ex-Ante Blindness, Ex-Post Coherence

On the subject of discovery, one awesome book I would recommend is Why Greatness Cannot be Planned.

In the book, the authors talk about how we need to think of any achievement as a process of discovery. They tell us to think of where we’re “looking for things” as a “search space.” The authors ask us to imagine a room full of inventions—the room has both inventions that have been found and the ones that are yet to be found.

If we think of the process of inventing as a process of searching through that room, then humanity has been exploring this space since the dawn of time. The more we explore it, the higher the chances of us finding something new.

But the thing is, we need a greater number of “stepping stones” to understand where the future might lie. The authors give us an example of ENIAC; when Thomas Edison was interested in vacuum tubes, he didn’t know one day it’ll be used as a computation device.

Similarly, microwave technology wasn’t discovered because someone was looking for it. It was found because, one day, Percy Spencer noticed that a magnetron—technology used earlier in radars—could melt his chocolate bar in his pocket. It became clear that microwaves were a stepping stones to ovens.

It’s evident: If you wanted to work on something like a “microwave” you wouldn’t have started working on radars.

Along the same lines, Steve Jobs, in his famous “connecting the dots” speech, talked about how, when he looked back at things they, started to make a better sense. Taking a calligraphy class just because he was interested in it made it possible for him to create the Graphical User Interface (GUI) for the Apple’s Lisa computer.

Multidisciplinarity is the “stepping stone” or the “dots” necessary for discovery, as inventions often happen on the edge of a discipline—especially when the process is multidimensional.

Helps You Understand The World Better

Multidisciplinarity is result of curiosity, and the best way to explore curiosity is to read. Reading exceptional books makes one thing quite clear: authors often think, research and extrapolate in a multidisciplinary manner.

I have been reading Guns, Germs and Steel4, in the book, Jared Diamond talks about how looking at an old question from new perspective requires you to think from a new point of view. You can’t “outsource” this; if you do, “the answers are incoherent at best and worthless at worst.”

Diamond writes how for us to better understand the human history, we need to understand various disciplines: genetics, molecular biology, biogeography to understand the crops; behavioural ecology to understand domestic animals; molecular biology to understand germs; Epidemiology to understand human diseases; linguistics, and archeological studies to understand the difference and similarities across cultures and continents and many more.

Looking at that list of disciplines, I’m glad he did the heavy lifting for us.

Part of the chapter below:

“This diversity of disciplines poses problems for would-be authors of a book aimed at answering a ‘multidisciplinary question’. The author must possess a range of expertise spanning the above disciplines, so that relevant advances can be synthesised. The history and prehistory of each continent must be similarly synthesised. The books subject matter is history, but the approach is that of science—in particular, that of historical science such as evolutionary biology and geology. The author must understand from the firsthand experience a range of human societies, from hunter-gatherer societies to modern space-age civilization.”

If we extrapolate the above paragraph we’ll notice a few things:

World is a complex place.

The environment around us doesn’t work in silos—think of the lollapalooza effect.

We can’t trust most researchers because most of them look at things from a mono-disciplinary perspective; hence, their conclusions are “incoherent at best and worthless at worst”.

And, if we want to understand something deeply, we will have to do it ourselves (most of the times)—beyond a point, we’ll have to be an autodidact.

In essence, reality is far messier than what a single discipline will ever be able to tell us. In the real world, everything plays/interacts with one another—we can’t put reality in silos. I think, Finance is the best discipline to understand this. (I will delve into detail in a later post.)

Dynamic Disequilibria

In real life, there are many forces at play at once, George Soros calls it “dynamic disequilibria”. If we go into the world with just a hammer, everything will look like a nail. To deal with reality, what we need is a “Swiss Army knife,” and multidisciplinarity is that knife.

Soros speaks on the geopolitical events of the early 1990s:

There are a number of processes going on concurrently and they interact. Usually they are perceived as external shocks, but in truth they may form integral parts of each other.

There is the emerging market boom and bust, the Mexican boom and bust, a separate story for each of the Latin American countries, the story about the yen and the Japanese market, the possibilities of a capitalist bust for Chinese communism, the tensions in Europe...

And underlying it all, there is a process of disintegration in the world that extends both to political and security issues and to economic and financial issues.

Cooperation among the monetary authorities is much weaker than it was at the time of the Plaza Accord. You don’t hear much about an emergency meeting of the G7 although there would be a lot to discuss. Each country pursues its own interests, sometimes individual institutions pursue their institutional interest, with little regard for the common interest. Yet, financial markets are inherently unstable and liable to break down unless stability is introduced as an explicit objective of government policy.5

My question to a mono-disciplinarian here is: How are you planning to “balkanize” reality? (See how I threw geopolitics in here?—Multidisciplinarity 101.)

Don’t be a one-legged man in an ass-kicking contest.

When Napoleon sailed for Egypt, he took with him 125 books on different subjects, including philosophy, geography, theology, biographies, poetry, drama.6 And the diversity was such that, he carried theological books as diverse as Bible and the Vedas.

Napoleon was well-versed in a lot of disciplines, an avid reader of history he once said, “Novels were for ladies’ maids; men should read history, nothing else.” While I don’t agree on the first part, I concur with the latter. If you want the ability to usefully navigate present and the ability to somewhat predict the future, you must know history—and not just one aspect of it but, from various points of view—this means reading and acquiring knowledge across disciplines.

As, George Santayana said, “Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.”

Similarly, Benjamin Franklin, was an avid devourer of books from different disciplines throughout his life—one of the reasons why Charlie Munger read him religiously.7 I love this quote from Leonardo da Vinci on the subject of multidisciplinarity: “Study the science of art. Study the art of science. Develop your senses—especially learn how to see. Realise that everything connects to everything else”.

The Iterative Blueprint

One of the modern men that I idealise is James Dyson. In one of his interactions, he said, “There were 5,126 failures, but I learned from each one. That's how I came up with a solution. So I don't mind failure”.

Think about it, Dyson iterated through 5,126 attempts until he had a marketable product. I adore Naval Ravikant’s take on this: “It’s not 10,000 hours but, 10,000 iterations”. The point is, if we haven’t experimented with a lot of different things or ventured into uncharted disciplines, we won’t have the perspective necessary to iterate effectively.

In conclusion

Read, think, and work across disciplines. Iteration and invention happens only when we think beyond the boundaries of what we already know.

An iterative mind thrives on the cliffs of limitation imposed by what it knows.

So: explore, experiment and expand the reaches of what you think you already know.

Try imagining this—it’s funnier.

Multidisciplinarity Definition: Multidisciplinarity applies to studying a subject from multiple different disciplines at the same time. Perspectives from the different disciplines create a broader understanding of a subject. Then, you try to integrate perspectives or insights from different perspectives through interaction, in order to better understand a complex phenomenon (or, lollapalooza effect). Integration can take place, for instance, at the level of methods, tools, concepts, theories, or insights

Read Jeff Bezos on building generational things.

Would 10/10 recommend the book.

Soros On Soros; Ch. Theory in Action

Napoleon A life, page 167-169.

Another might be the fact that one of Benjamin Franklin’s son also died quite young, and Munger would have probably related to Benjamin on that aspect of his life as well.